John Coakley Lettsom (1744–1815) seems to have been a nice sort of man. Born the son of a Quaker plantation owner in the Virgin Islands, he was sent to England at the age of six to be educated, and was eventually apprenticed to an apothecary in Settle, North Yorkshire, when an interest in botany was developed as he gathered medicinal plants on the moors. After five years, he went down to London, working as a surgeon’s assistant at St Thomas’s Hospital.

John Coakley Lettsom (1744–1815) seems to have been a nice sort of man. Born the son of a Quaker plantation owner in the Virgin Islands, he was sent to England at the age of six to be educated, and was eventually apprenticed to an apothecary in Settle, North Yorkshire, when an interest in botany was developed as he gathered medicinal plants on the moors. After five years, he went down to London, working as a surgeon’s assistant at St Thomas’s Hospital.

In 1767, he returned to the West Indies, having inherited a plantation from his father, but almost immediately freed all the slaves who worked it, thus leaving himself destitute (as he later described in a letter reproduced in the 1817 biography written by his protégé, the surgeon and antiquarian John Pettigrew, famous for his after-dinner unwrapping of mummies). He prospered as a physician in the Caribbean, but returned after a year to study medicine at Edinburgh, where he wrote a dissertation on the pathological effects of tea-drinking.

He became a very successful doctor in London, having many of the great and good as patients, being received by George III, and corresponding with (among others) George Washington, Erasmus Darwin and Benjamin Franklin. He worked extremely hard, both at his profession and on his many and varied interests and philanthropic projects. His concern about the deleterious effects of tea-drinking, first noticed in his Edinburgh dissertation, found further expression in The Natural History of the Tea Tree, with Observations on its Medical Qualities, and Effects of Tea-Drinking (1772), which we are about to reissue.

The book begins with a description of the plant using the Linnaean system, and discusses tea cultivation and harvesting in China, and the preparation of the leaves for use locally and abroad. In Part II, Lettsom turns to the medical uses of tea, lamenting that so little scientific evidence exists for either its beneficent or its malign properties. After performing various experiments and considering the physical and social consequences of tea-drinking, he concludes that it should be avoided, because its enervating effects lead to weakness and effeminacy – advice which mostly fell on deaf ears.

Lettsom was also a tireless pamphleteer. His collected short works were published in three volumes in 1802: the range of topics in which he took an interest and wanted to impart advice is given by the ODNB as ‘soup kitchens, beehives, poverty, discharged prisoners, prostitution, infectious fevers, a Samaritan society, crimes and punishments, wills and testaments, lying-in charities, deaf mute people, village societies, blind people, a society for promoting useful literature, hints to masters and mistresses, religious persecution, humane parties, Sunday schools, the Philanthropic Society, dispensaries, hydrophobia, sea-bathing infirmaries, and a substitute for wheat bread’.

Lettsom and his family in his garden at Camberwell. Note the hot-houses in the background. Credit: Wellcome Library, London

His hyperactivity, and his aristocratic clientele, made him the object of satirical gibes as a social climber: he was caricatured as ‘Dr Wriggle’, the protagonist in skit called ‘The art of rising in physic’. But he was also tireless in his philanthropy and his enthusiasm for the progress of science. He was one of the founders of the first free dispensary for the poor in London, of the Royal Humane Society, and of the Medical Society of London, to whom he gifted a house off Fleet Street as its headquarters. He had backed smallpox inoculation from its introduction, and was a warm supporter of Edward Jenner.

He was also very keen on new methods in agriculture, promoting, for example, the growing of mangel-wurzels in Britain: ‘I have ventured to order two hundred weight of seed from Paris’; it would be sold for a small profit ‘to be divided between the Society for the Relief of Small Debtors, and the Humane Society for Recovery of Drowned Persons’.

His book of advice for travellers of a scientific or inquiring disposition was first published in 1772; a second edition came out in 1774; a third edition was partly printed soon afterwards, but ‘various avocations then intervening, prevented the completion of the remaining sections; nor would this little performance have been now resumed’ if any superior work had come out in the intervening 25 years. The 1799 third edition mostly consists of exhortations to and instructions for ‘the many gentlemen and sea-faring persons’ who enjoy both time and opportunity for collecting the best information on ‘such subjects of general utility’ which they might overlook ‘for want of proper directions’.

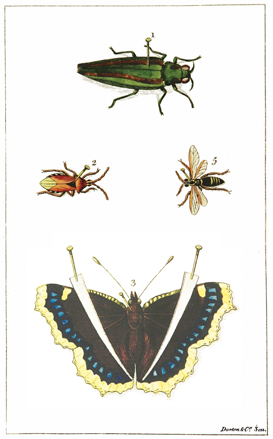

Lettsom gives detailed instructions for capturing and preserving insects, birds and animals so that they could be brought back for further study. A major problem was the preservation of animal tissue from moths and insects who thrived on the decaying skin and bones: it is interesting that all the compounds for which Lettsom gives recipes include tobacco among their ingredients, showing that the use of nicotine-derived insecticides is nothing new.

A ring-necked parakeet (above) and a golden-winged flycatcher (below). Watercolours by Lettsom, who was keen that travellers should attempt drawings of the specimens they observed. Credit: Wellcome Library, London

There are also instructions in drying and pressing or varnishing plants, and mounting them on paper, with details of plant name, place collected, soil time, time of year, etc., as well as methods for getting live plants safely back to England, some years before the Wardian case. The analysis of mineral springs is given much attention, as is the collection of soil samples and even gases. But the lives and customs of the people to be encountered abroad were also worthy of study. Lettsom’s Part II lists the sorts of questions which should be asked of the natives: ‘Observations and queries respecting learning, antiquities, religious rites, polite arts, etc.; commerce, manufactures, arts, trade, etc.; meteorological observations, food, way of living, animal oeconomy in general; zoology; botany; and mineralogy’.

The questions range from ‘To what genus and species does the grass called ‘Tatack’ belong?’ to ‘Have any buildings or ships, furnished with electrical rods after Dr Franklin’s method, ever received any injury from lightning?’ The traveller should also try to procure a good drawing of the sea-cow (or manatee), and/or get hold of any ‘manuscripts, in good preservation, of the Hebrew Bible, or parts thereof, particularly if upwards of 300 years old’.

The diligent traveller would have been completely exhausted – and with little time for any of the usual purposes of the Grand Tour – if he had fulfilled all of Lettsom’s instructions, and the amassing of specimens would have bulked up his luggage considerably. But by focusing on specific questions about the natural world and about the history and economy of foreign and exotic lands, Lettsom was far ahead of his time. He was, in a way, using the ‘wisdom of crowds’ to get answers to scientific problems by using laymen’s observations, and his belief that a wider knowledge of the world tends ‘to enlarge the human understanding, and to render individuals wiser, better and happier’ (along with his exclamation ‘Who will thank us for dying rich!’) show a nature than was truly philanthropic.

Caroline

What a comprehensive introduction to a little known historical figure, and his work. Thank you for the review.

And thanks for your very kind words!

Pingback: Treasured Possessions | Professor Hedgehog's Journal